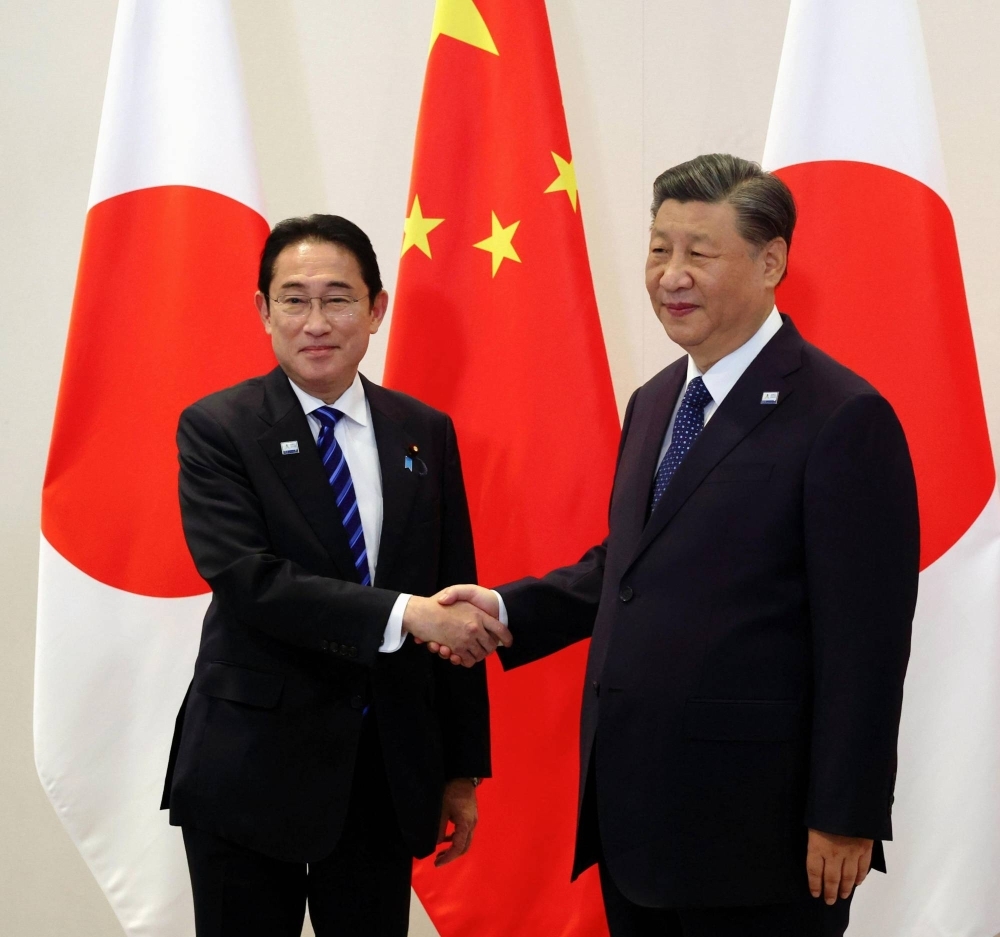

In their first meeting in a year, Prime Minister Fumio Kishida and Chinese President Xi Jinping on Thursday reaffirmed their commitment to “a mutually beneficial relationship” between Japan and China, despite a spate of deep rifts on issues such as national security and the economy.

The talks signaled initial momentum toward a cautious detente between the two neighbors, but didn’t result in any concrete progress over any divisive political issues, with the two countries appearing to prioritize an improvement in economic ties.

In his opening remarks, Kishida voiced his desire to work together to build a brighter future in bilateral relations.

“As neighbors who share a long history and a long future, Japan and China have a responsibility to coexist and prosper together, while contributing to world peace and stability as powers leading the region and the international community,” Kishida said, noting how this year marks the 45th anniversary of the signing of the Treaty of Peace and Friendship between the two countries.

Xi struck a similar note, emphasizing the necessity of handling divergent views “adequately” and grasping the “flow of the current times.”

“In a rapidly changing international situation, peaceful coexistence, long-standing friendship, mutually beneficial cooperation and joint development are in the interest of the people of both China and Japan,” the Chinese leader said.

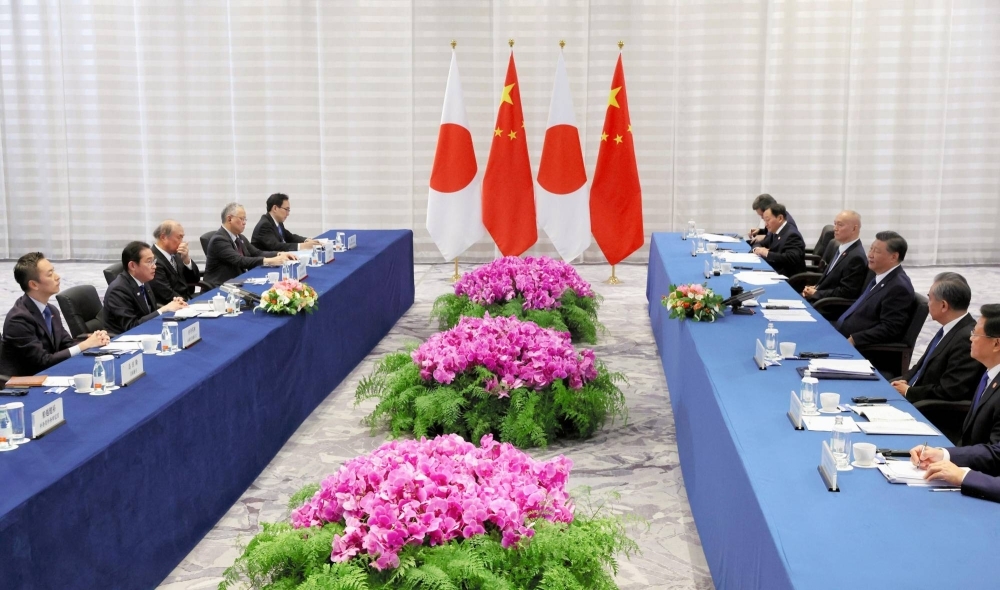

In the hourlong meeting on the sidelines of an Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation forum in San Francisco, the two leaders confirmed their continued efforts toward “the comprehensive promotion of a mutually beneficial relationship based on common strategic interests,” a cooperation framework established in 2006 and formalized in a joint statement two years later.

That framework defines the relation between Japan and China as “one of the most important bilateral relationships” for the two countries and enshrines cooperation to enhance peace and friendship as the two countries’ “sole option.”

Kishida and Xi also agreed to establish a new dialogue framework on trade, a move that comes amid ongoing restrictions on semiconductors and other key technological components.

The Kishida-Xi summit also came on the same day that Japanese Foreign Minister Yoko Kamikawa confirmed that Tokyo, Beijing and Seoul plan to resume high-level talks, although a date for a trilateral foreign ministers meeting has yet to be determined.

However, despite the conciliatory tone seen in the meeting, the relationship between Beijing and Tokyo has tumbled to fresh lows since the two leaders met in Bangkok a year ago.

In late August, Beijing implemented a blanket ban on all Japanese seafood following Tokyo’s decision to release 1.3 million tons of treated water from the crippled Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant. The restrictions struck a blow to Japan’s marine sector — especially that of Hokkaido — and irked Tokyo, which issued a formal complaint and threatened to bring the case to the World Trade Organization.

Since then, the two countries have repeatedly clashed at international meetings, with China vehemently condemning the release of what it claims to be “nuclear-contaminated water” and Japan demanding an immediate lift of what it calls an unscientific measure.

Speaking to reporters after the meeting, Kishida said the two leaders agreed to address the issue through dialogue and consultation "based on science" and at an "expert level,” but fell short of charting a concrete path toward a solution.

In 2022, China and Hong Kong represented the two largest markets for Japan’s fishing industry, with exports amounting to 42% of total sales overseas. That same year, Beijing was Japan’s largest trading partner, well ahead of the United States.

That said, a Chinese concession to lift the seafood restrictions at this stage was always seen as unlikely.

“China doesn’t tend to reverse these trade decisions quite so quickly, especially only a few months after sounding a red alarm,” said Chase Blazek, Asia-Pacific analyst at U.S.-based geopolitics and intelligence firm RANE, pointing out that from Beijing’s perspective this is mainly a political gesture, particularly as Japanese marine products make up a surprisingly small portion of China’s total seafood imports.

At the heart of the matter, he argued, are a number of strategic issues affecting the relationship, including Japan’s efforts to boost regional military partnerships to deter China, as well as recent statements that the security of Taiwan — which Beijing regards as a breakaway province — is critical to the security of the wider region and the world.

During the talks with Xi, Kishida reiterated his concerns over China’s military operations in the region and demanded the removal of a buoy installed in Japan’s exclusive economic zone.

But perhaps the biggest takeaway from these and previous talks between the two sides in San Francisco was their willingness to temporarily put aside political disagreements and focus on getting their economic and trade relations back on track.

On Tuesday, the countries’ economy ministers agreed to set up a framework to discuss export controls, with the aim of facilitating conversations on policy, including potential changes to trade and economic engagement strategies.

But an outstanding question is the role of U.S. policy in Sino-Japanese ties. Washington has set the tone by being first to set the recent export controls, which Japan agreed to join earlier this year. The move saw Tokyo impose restrictions on 23 chipmaking tools to align with a U.S. policy aimed at restricting China's ability to produce advanced semiconductors.

That said, a major difference between Japanese and American export controls is that the U.S. rules are aimed specifically at China, whereas Tokyo’s licensing changes are country agnostic. This could provide Japan with additional room to make progress on trade relations with China, said Emily Benson, an international trade expert at the Washington-based Center for Strategic and International Studies, with Beijing having tightened export controls on gallium and germanium, two elements needed to make chips.

The economy ministers also agreed to set up a working group to improve the business environment, with this encompassing moves to ensure the safety of Japanese businesspeople in China. The case of a Japanese executive of a pharmaceutical company who was sentenced to 12 years in a Chinese prison on espionage charges has worsened already strained business ties and shone the spotlight on the number of Japanese nationals jailed in the country.

One of the main drivers behind Beijing’s conciliatory tone appears to have been the ongoing economic slowdown in China.

“China’s economic difficulties and their implications for social stability and regime legitimacy have made Beijing more eager to improve relations with countries important to its economy than was the case six to 12 months ago,” said Thomas Fingar, an East Asia expert at Stanford University.

The Chinese economy is facing a combination of challenges that have shaken consumer confidence, with these including turmoil in the real estate sector and high youth unemployment.

“With domestic demand constrained in these ways, foreign trade is essential for the Chinese economy,” said Willem Thorbecke, a senior fellow at the Tokyo-based Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry.

“Chinese leaders realize this and want to mend bridges,” he added.

At the same time, Beijing seems to be trying to persuade Tokyo not to oppose its bid to join the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership, a free-trade pact that would improve Chinese access to key regional markets.

That said, policymakers in Tokyo cannot afford to be complacent either, as Japanese gross domestic product contracted by an annualized 2.1% in the July-September period.

“China is a lucrative market with 1.4 billion consumers and businesses that want Japanese capital goods, components and products, so Japanese policymakers would like to remove anything that hinders trade with China,” Thorbecke noted.

Although Japan and China remain at loggerheads over several strategic issues, experts believe the relationship could make real progress if the two sides manage to build on the recent diplomatic momentum for future meetings and trade talks, especially as the U.S. presidential election approaches.

“There’s a real fear in many Asian capitals, especially those of U.S. allies like Japan and South Korea, that the return of a Donald Trump presidency could revive unpredictable and unsteady ties with Washington,” said Blazek. As a result, he said, many Asian countries will try to hedge their bets regionally by improving foreign ties where they can.

“Japan and China won’t become friends again overnight, as they have too much strategic baggage,” said the RANE analyst. But there is precedent for Tokyo “holding its nose to maintain and even improve economic ties with China, even as it deepens security partnerships to counterbalance against China’s growing military might.”

culled from Japan Times